For all his devotion to higher education, the road my grandfather took to the bachelor’s degree was long and winding. As I wrote in Part One of this post, he had only a ninth grade education when, in 1917, at the age of 20, he enlisted in the U.S. Navy during World War I and spent the next two years crisscrossing the Atlantic Ocean as a radio electrician on the supply ship U.S.S. Tivives. In the Navy, he learned to send and receive continental Morse Code, taking classes at Great Lakes Naval Training Station in Chicago and the Naval Radio School at Harvard. He must have glimpsed, during this time, what a higher education involved and what doors it opened – and he must have seen that, country boy that he was, he was as capable of advanced learning as any other.

It was also during this time that he received his call to the ministry. What happened in the Navy that steered my grandfather towards a religious vocation? Perhaps he saw things in the training camps and onboard ship that shocked him. Perhaps, suffering from homesickness, he found comfort in his faith. Perhaps his regular reading of the Bible sustained him in ways he would never forget.

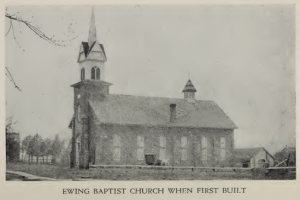

In any case, a year or so after returning to Honey Bend, Illinois, in late 1919, Russell Wallis left home again, this time for the “preparatory department” of Ewing College, a small, Baptist school about 120 miles away, deeper into southern Illinois, and the world of Southern Baptists, than he had ever been. For the first time, he was surrounded by men and women intensely dedicated to a life of religious study and service. It must have been affecting: all the theological debates, Bible preaching, and gospel singing – all the conversions, baptisms, and revivals.

The school was small, with only 15 faculty members, 300 students, and five buildings. It included both an academy (the preparatory department) and a college. And it was coeducational, which is how my grandfather met my grandmother there in the early 1920s. The school was also always teetering on the edge of bankruptcy. Still, it was known to be a “poor man’s school” – as a later history of the college put it, “No worthy student, even if he were penniless, was ever turned away” (131).

But more than anything, Ewing was devoted to the Bible:

The Bible was the pre-eminent text book in Ewing College. Whatever else a student might take, he was required to take Bible. But this was not all. The administration held that not only should the Bible be taught by noble God-fearing men, but that science and mathematics, history and English, should also be taught by men and women who were devoutly religious. The presence of God was felt in every class room. (130)

Even its rural location was thought to support the school’s religious focus: according to a 1912 history of Southern Illinois, “Ewing is not on any railroad and the town is small and these facts are urged as advantages in sending young people to school” (385).

During his time at Ewing, Russell Wallis not only studied, he also preached, though probably not until his second or third year there and probably only on the weekends. He did it, of course, to serve the Lord, but also, no doubt, to make a little money, though it’s hard to imagine he made much from the little country church he served – Mulberry Grove Baptist in Mulberry Grove, Illinois.

Soon after being ordained at Mulberry Grove, my grandfather, then 26 years old, married Prudence Elizabeth Douthit, whom he had met a couple of years earlier at Ewing. She was born on April 2, 1904, in South Muddy Township, Jasper County, Illinois, the eldest daughter of Ira Clarence Douthit and Dora Ann Blunk. Like Russell, she was smart and devout and from a large, rural family. Though seven years his junior, she finished high school before he did, spending a year or two as a teacher in a village near her home while he continued his studies at Ewing. The two were married on September 4, 1923, in Salem, Illinois, and would be together for more than 60 years.

Throughout 1924, my grandfather studied during the week and preached on the weekends, with Prudence in the front row. The couple lived in Ewing, where their first child, Helen Louise Wallis, was born on April 2, 1925, her mother’s twenty-first birthday. By that point, Russell had graduated from the preparatory department and was well into his college studies, which included Bible, Greek, Latin, mathematics, and English.

My grandfather would look back on his time at Ewing fondly; nearly 35 years later, while pastor at First Baptist Church of Litchfield, Illinois, he would help found the college’s first alumni organization, help organize its first reunion, and help initiate its first written history. But, in fact, Russell Wallis didn’t actually complete his college education at Ewing – there was still one more bump on the way to his bachelor’s degree. In 1925, Ewing College closed, a victim of its long-standing fiscal problems.

So, sometime in 1925, my grandfather moved with his small family to Liberty, Missouri, to enroll at William Jewell College. Like Ewing, it was founded after the Civil War and had deep Baptist roots; it also had a similar course of study and thus permitted an easy transfer for Russell. As far as I can tell, he attended Jewell for two years, graduating with the Bachelor of Arts degree in the spring of 1927, at the age of 30. According to a short biographical statement about my grandfather in the History of First Baptist Church of Marion, Illinois, he pastored churches in Missouri while at William Jewell, just as he had done at Ewing.

By now, my grandfather had clearly caught the academic bug – he wanted more. So the family moved next to Texas, where he could do graduate work at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary (SWBTS) in Fort Worth. The dates here have been somewhat difficult to reconstruct, but I know that Russell and Prudence’s second child, Elizabeth Ann Wallis, was born on November 21, 1927, in Fort Worth and that the family was still in Texas three years later for the 1930 U.S. Census, though Russell would begin his first major pastorate in Marion, Illinois, in October of that year. From these dates, I surmise that my grandfather attended SWBTS from 1927 to 1930 and was awarded the Master of Divinity (M.Div.) degree at the end of that period.

The move to Southwestern was a sign that my grandfather wanted to be more than a country preacher – he wanted to be a learned minister, and he wanted to do so under the auspices of the Southern Baptist Convention. His allegiance was now clearly shifting away from his agricultural roots in rural Illinois and toward a larger world of faith, service, and pastoral vocation.

Southwestern Baptist Seminary was an outgrowth of the theological department at Baylor University in Waco, Texas. In 1905, under the leadership of Prof. B. H. Carroll, the department became Baylor Theological Seminary; and, in 1907, the Baptist General Convention of Texas authorized the separation of the seminary from the university. SWBTS was chartered on March 14, 1908, though it remained on the Baylor campus until the summer of 1910, when it accepted an offer from the citizens of Fort Worth, Texas, to re-locate there. Dr. Carroll was the seminary’s first president, serving until his death in November, 1914. The second president, L. R. Scarborough, served for more than a quarter century, from 1915 to 1942, overseeing the 1925 transfer of the seminary from the Baptist General Convention of Texas to the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC), the denomination’s national association. Today, Southwestern is one of the largest seminaries in the world and has trained more than 42,000 graduates to serve in churches and missions around the globe.

At SWBTS, my grandfather was surrounded by some of the best known preachers and theologians in the Southern Baptist universe. They were men both learned and pious, scholarly and devout. He must have been deeply influenced by President Scarborough, who was himself devoted to his predecessor, B. H. Carroll. In a 1930 introduction to a book by Carroll, Scarborough wrote, in words that must have appealed to my grandfather:

My faith is the faith of a simple, plain Baptist. I accepted from my father and Dr. B. H. Carroll the verbal inspiration of the Bible, the deity of Jesus Christ, His perfect humanity, His atoning death, His bodily resurrection, His second coming. All my studies since have confirmed the simple faith I received from them.

There was also J. B. Tidwell, popular professor of the Bible at Baylor from 1910 to 1946, and the Rev. George W. Truett, well-known pastor of First Baptist Church of Dallas from 1897 to 1944 and president of the Southern Baptist Convention from 1927 to 1929. According to my father, Truett’s preaching made a lasting impact on Russell Wallis.

The 1920s was, in fact, a lively time to be studying at a Baptist seminary in the United States. I wrote in Part One of this post about the 1907 schism in the Illinois Baptist State Convention and the subsequent affiliation of Baptists in the southern part of that state with the SBC. And I wrote about the wider resurgence of conservative Christianity then, especially in the rural South and Midwest, a reaction, according to Wikipedia, against the “theological liberalism and cultural modernism” of the time.

The term “fundamentalism” is important for understanding the background of my grandfather’s theological education in the 1920s and his subsequent ministry, though its meaning has changed since it was first coined in 1920. In my opinion, it both applies and doesn’t apply to my grandfather in ways that have been important, for me at least, to tease out.

In his article “The Rise of Fundamentalism,” Professor Grant Wacker of Duke University’s Divinity School distinguishes between “fundamentalism as a generic or worldwide phenomenon” and “Fundamentalism as a religious movement specific to Protestant culture in the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.” The former, writes Wacker, “refers to a global religious impulse, particularly evident in the twentieth century, that seeks to recover and publicly institutionalize aspects of the past that modern life has obscured. It typically sees the secular state as the primary enemy . . . [and] takes its cues from a sacred text that stands above criticism.”

“Historic Fundamentalism,” by contrast, “shared all of the assumptions of generic fundamentalism but also reflected several concerns particular to the religious setting of the United States at the turn of the century. Some of those concerns stemmed from broad changes in the culture such as growing awareness of world religions, the teaching of human evolution and, above all, the rise of biblical higher criticism. The last proved particularly troubling because it implied the absence of the supernatural and the purely human authorship of scripture.” Wacker continues:

Social changes of the early twentieth century also fed the flames of protest . . . Fundamentalists felt displaced by the waves of non-Protestant immigrants from southern and eastern Europe flooding America’s cities. They believed they had been betrayed by American statesmen who led the nation into an irresolved war with Germany, the cradle of destructive biblical criticism. They deplored the teaching of evolution in public schools, which they paid for with their taxes, and resented the elitism of professional educators who seemed often to scorn the values of traditional Christian families.

An important event in the rise of Christian Fundamentalism in the United States was the release, between 1910 and 1915, of The Fundamentals, a twelve-volume set of essays written by conservative Protestant theologians defending what they saw as Protestant orthodoxy. According to Wikipedia, the essays stressed several core beliefs of conservative Christianity, including “the inerrancy of the Bible; the literal nature of the Biblical accounts, especially regarding Christ’s miracles and the Creation account in Genesis; the Virgin Birth of Christ; the bodily resurrection and physical return of Christ; and the substitutionary atonement of Christ on the cross.”

The term “fundamentalist” was coined by Baptist editor Curtis Lee Laws in 1920 “to designate Christians who were ready ‘to do battle royal for the Fundamentals.’” The movement was especially prominent in the 1920s among U.S. Baptists and Presbyterians, though it didn’t appeal to all. A counter-attack came in 1922 when Baptist preacher Harry Emerson Fosdick delivered a much-heard sermon at First Presbyterian Church of Manhattan, titled “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?”

A key year in the debate between “fundamentalists” and “modernists” was 1925. That was the year Southwestern Seminary came under the control of the SBC, and it was the year of the so-called Scopes Monkey Trial, when the teaching of evolution was denounced by William Jennings Bryan, whose mother was Southern Baptist and whose hometown was Salem, Illinois, where my grandparents married. The year 1925 was also when Southern Baptists published their first formal confession of faith. The SBC had no such statement until theologian E. Y. Mullins led the denomination to adopt the “Baptist Faith and Message” (BF&M) of 1925, which in its preamble alluded to the fundamentalist-modernist debate: “The present occasion for a reaffirmation of Christian fundamentals is the prevalence of naturalism in the modern teaching and preaching of religion. Christianity is supernatural in its origin and history. We repudiate every theory of religion which denies the supernatural elements in our faith.”

Article I of the 1925 BF&M included the following statement:

We believe that the Holy Bible was written by men divinely inspired, and is a perfect treasure of heavenly instruction; that it has God for its author, salvation for its end, and truth, without any mixture of error, for its matter; that it reveals the principles by which God will judge us; and therefore is, and will remain to the end of the world, the true center of Christian union, and the supreme standard by which all human conduct, creeds and religious opinions should be tried.

Protestant fundamentalism of the 1910s and ‘20s thus saw itself as a reaction against several perceived doctrinal and cultural threats. One of these was the “higher criticism” of the Bible, as practiced at places like the Baptist-affiliated University of Chicago. At a 1912 meeting of the Kaskaskia Baptist Association at Mulberry Grove Baptist, my grandfather’s first church, the assembled ministers proclaimed: “We urge our young people, and especially our preachers, to seek to obtain as good an education as possible, and we recommend Ewing and Shurtleff Colleges as the place to obtain it. We warn all our people to beware of the sink of infidelity called the University of Chicago” (111).

Other threats that spurred the rise of Christian fundamentalism in the United States in the early twentieth century included the sale and consumption of alcohol and the teaching of evolution in the public schools.

Where did my grandfather stand on these issues? He was definitely a scripture man – everyone who knew him or heard him preach has talked of his deep devotion to and knowledge of the Bible. He was also an avid supporter of temperance; when I was growing up in the 1960s and ‘70s, he didn’t even drink Coca Cola. As for the theory of evolution, I never heard him say a word about it, good or ill. But, however else he aligned, or didn’t align, with fundamentalists, Russell Wallis was not militant in the way Curtis Lee Laws meant when he coined the term; he was not a fighter in some “battle royal” between true and false Christians or between the saved and the damned. He was by nature a gentle, humble man, and by vocation a devoted pastor and expositor of the Bible.

In other words, my grandfather was not politically conservative in the sense that would apply to Christian fundamentalists of the later twentieth century, especially after 1979, when the Southern Baptist Convention took a hard right turn. This distinction between fundamentalism of the 1910s and ‘20s and that of the 1970s and ‘80s (and today) is drawn nicely in the article on “Christian Fundamentalism in the United States” in the Encyclopedia Britannica:

Fundamentalists opposed the teaching of the theory of biological evolution in the public schools and supported the temperance movement against the sale and consumption of intoxicating liquor. Nevertheless, for much of the 20th century, Christian fundamentalism in the United States was not primarily a political movement. Indeed, from the late 1920s until the late 1970s, most Christian fundamentalists avoided the political arena, which they viewed as a sinful domain controlled by non-Christians.

• • •

Clearly, my grandfather studied for the ministry during a time of intense social and cultural upheaval, when the forces of past and future, conservative and liberal, sacred and secular, hinterland and city, seemed to be at loggerheads. There’s no question that, in most respects, Russell Wallis was on the side of the conservatives in this debate. I’m sure he subscribed to the Baptist Faith & Message in its entirety for most of his ministerial career. But he was not “fundamentalist” in the sense that that word acquired at the end of the twentieth century.

His ministry can perhaps best be summed up by quoting the opening chapter of the First Epistle of Peter, a favorite of my grandfather’s. It’s an apt passage not only for its evocation of Christian faith – that belief in one “whom having not seen, ye love” – but also for its deeply pastoral quality, written as it was, metaphorically speaking, by a shepherd to his flock: reassuring, comforting, reminding, and inspiring them.

3 Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, which according to his abundant mercy hath begotten us again unto a lively hope by the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead,

4 To an inheritance incorruptible, and undefiled, and that fadeth not away, reserved in heaven for you,

5 Who are kept by the power of God through faith unto salvation ready to be revealed in the last time.

6 Wherein ye greatly rejoice, though now for a season, if need be, ye are in heaviness through manifold temptations:

7 That the trial of your faith, being much more precious than of gold that perisheth, though it be tried with fire, might be found unto praise and honour and glory at the appearing of Jesus Christ:

8 Whom having not seen, ye love; in whom, though now ye see him not, yet believing, ye rejoice with joy unspeakable and full of glory:

9 Receiving the end of your faith, even the salvation of your souls.

• • •

While studying at Southwestern in the late 1920s – as at Ewing and William Jewel Colleges before – Russell Wallis also preached at local churches on the weekends. Of course, churches at the time (1927-1930) couldn’t afford much in the way of minister salaries, and my grandfather was now not only supporting himself but also a wife and two little girls. My aunt Helen has seen letters he wrote to Honey Bend at this time, asking his parents for financial help.

In 1930, he finished the M.Div. degree at Southwestern. He had spent the entire decade of the 1920s in Baptist schools preparing for the ministry, and his life as a learned pastor was, finally, about to begin.

My grandfather was associated with numerous religious communities in the more than half a century of his active career, playing a leading role in a dozen or more churches and missions. But there were, by my count, five major pastorates, each lasting five or more years. The first would take him and his family back to southern Illinois.

On October 1, 1930, Russell Wallis, 33 years old, husband, father, and now holder of both A.B. and M.Div. degrees, became pastor of the large and well-known First Baptist Church of Marion, Illinois. He would remain there with his family for the next five years.

Founded in 1865, First Baptist of Marion was a prominent church in the history of southern Illinois Baptists. The leader of the 1907 secession of southern Illinois Baptists to the SBC, W. P. Throgmorton, was himself pastor at Marion from 1904-06 and again from 1913-18. My guess is that my grandfather knew Throgmorton, or at least heard him preach.

The church in Marion was at 401 West Union Street, where it remains to this day. The structure my grandfather knew, the second in the church’s history, was built in 1913 and can be seen above. That building has since been replaced by a newer structure, shown below.

According to a 1965 history of the church, the parsonage of First Baptist Marion was just around the corner on North Monroe Street; it was later moved, in 1952, to West Union Street to make room for a new education building. In the early 1930s, both church and parsonage were near the town square in downtown Marion.

When my grandfather assumed the pastorate at First Baptist Marion, it was the height of the Great Depression, and the downtown location of the church attracted a steady stream of beggars to the parsonage. My aunt Helen, the eldest child, has vivid memories of this time. She says that homeless men were often knocking on the door, asking the minister’s family for help. Her father never gave the men money; but, according to Helen, he always made sure they were well-fed. He had an arrangement with a nearby restaurant, in fact, to give the men food; the owner kept a tab, which my grandfather always paid. In this, of course, he was following a Biblical injunction:

For I was an hungred, and ye gave me meat: I was thirsty, and ye gave me drink: I was a stranger, and ye took me in. (Matthew 25:35)

Even little Helen tried to feed the hungry during these hard times, though she was only 5-10 years old when the family lived in Marion. One day, alone at the parsonage when a beggar came to the door, she fixed him a fried egg sandwich, which she later found in the front yard – it was apparently not to the man’s liking.

Ironically, although it was the Depression, First Baptist Marion was the grandest church my grandfather had ever served; and the parsonage on North Monroe Street, the biggest house he, his wife, and daughters had ever lived in.

Still, times were hard, even for the reverend and his family. My grandfather took seriously his pastoral duties, putting the needs of the flock before his own. In H. Lee Swope’s 1965 History of the First Baptist Church of Marion, Illinois, the Depression years are described this way:

The church was fortunate to have as her pastor the warm-hearted, gentle-spirited R. W. Wallis during these difficult days. He voluntarily reduced his salary, which was already very low, to help the financial strain. He moved quietly among his people with a true Christian spirit and led them slowly, but surely, to increases in enrollment, attendances and gifts. (14)

“[T]he warm-hearted, gentle-spirited R. W. Wallis” – I don’t know where Reverend Swope got these words, since he was writing thirty years after my grandfather left Marion, but they are as true a description of him as I’ve ever read. Perhaps that’s why this particular church, of all my grandfather’s pastorates, holds a special place in my heart, though that could also be because my mother, Nancy Jo Wallis, was born in Marion on May 31, 1932. She was Russell and Prudence’s last born child. The family now numbered five.

After two years in Missouri and three years in Texas, the family was finally back in southern Illinois, near the Wallis and Douthit extended families. My grandfather must have taken his wife and daughters to visit Honey Bend. They would have sat on the porch of his parents’ farmhouse and watched the cars and trucks go by on U.S. Route 66, the new automobile highway that stretched from Chicago to Los Angeles and which, beginning in 1930, passed between Springfield and St. Louis right where I-55 now travels. In the 1930 map below, you can see how the famous road literally bisected the Wallis farm in Zanesville Township.

In late 1935, after more than five years of devoted service, my grandfather resigned his position at First Baptist Marion and took a new position as pastor of Moffett Memorial Baptist Church in Danville, Virginia, a church which had been founded in 1887. The family would be in Danville from January, 1936, until August, 1940.

Below is a photograph of the church, at 1026 North Main Street, where my grandfather preached for nearly five years.

In June, 1971, a fire consumed the 82-year-old structure, and eventually a new church, standing today, was built in its place.

In June, 1971, a fire consumed the 82-year-old structure, and eventually a new church, standing today, was built in its place.

My grandfather was the seventh pastor at Moffett, which had a membership of about 800 when he was there. According to V. E. Mantiply’s 1987 history, large crowds attended prayer services there on Wednesday nights; and “the church kept up its reputation as a temperance church during these years, and tried hard to overthrow the liquor traffic in Virginia.”

My mother, who was between 4 and 9 years old when the family was in Danville, has especially fond memories of the church janitor, Arthur, who let her ride on his shoulders when he turned off the lights after services on Wednesday and Sunday nights. Prudence, meanwhile, attended nearby Averett College, trying to finish her own college education. In the mornings, my grandfather made oatmeal for everyone; before eating, the family always read the Bible together.

My mother, who was between 4 and 9 years old when the family was in Danville, has especially fond memories of the church janitor, Arthur, who let her ride on his shoulders when he turned off the lights after services on Wednesday and Sunday nights. Prudence, meanwhile, attended nearby Averett College, trying to finish her own college education. In the mornings, my grandfather made oatmeal for everyone; before eating, the family always read the Bible together.

In the 1940 U.S. Census, the Wallises are still in Danville, living in the parsonage at 1024 North Main Street, but they would soon be leaving. My grandfather resigned the pastorate at Moffett Memorial in August, 1940, to return to school. As at Marion before, Russell served the Danville church for five years before moving on. It would be a pattern he would follow his whole career.

Why did he move so often? When I asked my mother and her sisters this question, they all answered the same way – my grandfather thought that five years was long enough for a pastorate, that churches benefitted from a new pastor every once in a while, just as pastors benefitted from new challenges. Russell Wallis thought a church should not become too dependent on its pastor and that a pastor should not grow too possessive of his church. A minister’s vocation, after all, was to serve, not to rule.

In Marilynne Robinson’s novel Gilead, a book that always reminded me of my grandfather, the old pastor John Ames recognizes at one point that his anxiety for his church is “a forgetfulness of the fact that Christ is Himself the pastor of His people and a faithful presence among them through all generations.”

That said, it must have been difficult for Prudence and the girls; yet I never once heard my mother or her sisters complain about the moving around they did as children, literally packing up every five years for a new city, a new school, a new life. It’s also true, as a colleague remarked to me recently, that, in those days, coming into town as the new pastor’s family and settling in the church parsonage was not the worst way to start a new life. In any case, my grandfather’s itinerant ministry has always intrigued, even puzzled, me – though the one thing I am sure about is that whatever he did, he did with great thoughtfulness.

After Danville, my grandfather’s family moved back to Texas so he could work on his doctorate in theology at Southwestern. They lived from 1940 to 1942 in Fort Worth while Russell studied, their second residence on Seminary Hill. On weekends, he was a pastor at area churches: from 1940-41 at First Baptist Church of Granbury; later, at First Baptist Church of Ponder. Prudence, meanwhile, attended graduate school at Texas Wesleyan College. In fact, in Texas, all five members of the family were in school: my mother, aged 8-10, in elementary school; Ann, 13-15, in junior high; Helen, 15-17, in high school; Prudence, at Texas Wesleyan, pursuing her master’s degree; and Russell, at Southwestern, studying for his Th.D.

After Danville, my grandfather’s family moved back to Texas so he could work on his doctorate in theology at Southwestern. They lived from 1940 to 1942 in Fort Worth while Russell studied, their second residence on Seminary Hill. On weekends, he was a pastor at area churches: from 1940-41 at First Baptist Church of Granbury; later, at First Baptist Church of Ponder. Prudence, meanwhile, attended graduate school at Texas Wesleyan College. In fact, in Texas, all five members of the family were in school: my mother, aged 8-10, in elementary school; Ann, 13-15, in junior high; Helen, 15-17, in high school; Prudence, at Texas Wesleyan, pursuing her master’s degree; and Russell, at Southwestern, studying for his Th.D.

After my grandfather finished the two years of his doctoral residency, the family moved again, this time to Russell Wallis’s third major pastorate, Park View Baptist Church in Portsmouth, Virginia, a church which had been founded in 1898. He would serve this church for five years, from 1942 to 1947.

The church building, at 225 Hatton Street, can still be seen today, although Park View Baptist itself closed in 2010.

The parsonage was at 309 North Hatton. The family were now in one of the busiest centers of U.S. military life during the greatest war the country has ever fought. The Park View Church was, and is, near both the U.S. Naval Shipyard and the U.S. Naval Hospital. My mother, 10-15 years old while the family was in Portsmouth, remembers well the air raid sirens, the “brown outs,” the sailors walking by, and her father getting a phone call one day from the Red Cross, informing him that one of the boys from the church, then serving overseas, had been killed. He was the one to tell the parents.

Helen, who was between 17 and 22 years old in Portsmouth, met a local boy, William DeWitt Rusher, who was also a U.S. serviceman, soon to leave for the European theater. My mother, only 10-15 at the time, thought of Bill as her “hero” and remembers vividly the day when he came home from the war. It must have been the summer or fall of 1945; she was hanging laundry outside. She says she will never forget the sight of him walking up the street to the parsonage to see Helen and the family. It must have seemed that the war was finally over and that the family could now exhale.

Russell remained at Portsmouth until the fall of 1947 before moving on again, this time back to Illinois. Only Prudence and Nancy accompanied him, however, since Helen and Ann were now away at school, finishing their own bachelor’s degrees at Meredith College (formerly Baptist Female University) in Raleigh, North Carolina.

Soon after moving, Russell, now 51 years old, finally finished his Th.D. dissertation, titled The Holy Spirit as Related to the Person and Work of Christ.

It is a theological examination of a central but complex Christian doctrine, the trinity – the three distinct but co-equal and co-eternal persons of the God-head: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Russell’s study deals with the relations of the Holy Spirit to the promised Messiah of the Old Testament, the Christ of the incarnation, and the glorified Lord, one long chapter devoted to each of these theological problems.

As such, the work involves detailed scholarly investigation of both Old and New Testaments, including relevant passages in their original languages. In fact, Russell was by now fluent in scriptural exegesis and could read the Bible in both Hebrew and Greek. When he died, my grandmother gave me two of his books: Socrates, by A. E. Taylor, which he was apparently reading at the time of his death, and his Greek New Testament, which is one of my prized possessions.

For me, a favorite passage of my grandfather’s thesis occurs early, in one of the few places in the text where one can feel the “gentle-spirited, warm-hearted” Russell Wallis shining through the scholarly and theological argument:

In seeking to trace the relation of the Holy Spirit to the person and work of Christ, the writer of this thesis is fully aware of the magnitude of the task and the possibility of making serious errors. It is not with any sense of personal fitness that the effort is attempted. the purpose of the thesis is the desire to seek a better understanding of the wonders of spiritual activity that make available to the needy heart of man the unsearchable riches of God’s grace in Christ. (9)

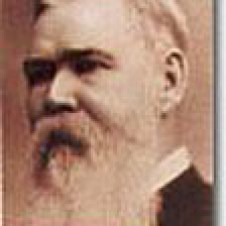

In any case, it was as Doctor Russell Wallis that my grandfather served for the next five years at his fourth major pastorate: Harrisburg Baptist Church in Harrisburg, Illinois, a church organized in 1868. The local newspaper, the Daily Register, announced the beginning of this pastorate on October 7, 1947. The following year, Russell not only completed his Th.D. dissertation; he also officiated, on December 26, 1948, at the double wedding ceremony of his two eldest daughters: Helen to Bill Rusher and Ann to Earl Fleetwood Stephenson. The two couples celebrated their honeymoons in separate hotels in St. Louis.

In Harrisburg, meanwhile, my grandparents and their youngest daughter Nancy lived at 8 East Walnut Street, near the church at 204 North Main. The church building still stands today, having celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2012.

While in Harrisburg, Prudence, increasingly active in her own right as her daughters grew up, served as president of the Women’s Missionary Union of the Illinois Baptist State Association. My mother, meanwhile, finished high school in Harrisburg and then headed off to college, first to Blue Mountain in Mississippi, then to Meredith, like her sisters, where she eventually met my father, a student at North Carolina State.

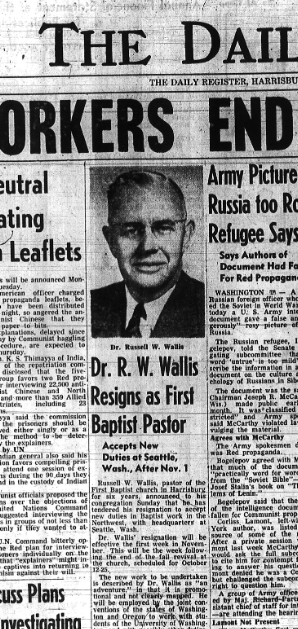

Just a few months after my parents were married on June 1, 1953, Russell resigned his pastorate in Harrisburg, having served this church for six years. The local newspaper treated the resignation as front-page news.

Russell and Prudence now embarked on a true adventure. Always interested in mission work, Russell accepted in late 1953 a post with the fledging Southern Baptist association of Washington and Oregon to work with students at the University of Washington in Seattle. What did he do there? Was the goal to organize a Baptist Student Union at the school? Did he hold prayer meetings and lead Bible classes? The period is something of a mystery to me.

After two years in Seattle, the couple moved back to Texas to teach at Baylor, Prudence in the English Department and Russell in Religion. They did this from 1955 to 1957. I’m not sure why they didn’t stay longer; in some ways, my grandfather was more a scholar than a preacher, and I think he must have been a caring and devoted teacher. My mother thinks having a Th.D. rather than a Ph.D. may have held him back in academia.

In any case, my grandfather’s next, and fifth, major pastorate was just a few miles from where he grew up. In 1957, he became pastor of First Baptist Church of Litchfield, Illinois. This church was organized in 1856 and located at 608 North Van Buren Street. The building shown here has since been demolished and a new structure erected.

It would be my grandfather’s last major pastorate. When, in 1962, he resigned this post after five years, he was 65 years old. He would continue to serve in interim and guest positions for another two decades, though his most important pastorates and missions were now behind him.

How many sermons did he preach in all that time? How many Sunday and Wednesday night services did he lead? How many Bible classes did he teach? At how many baptisms, weddings, and funerals did he officiate? How many benedictions and prayers did he give? The length and breadth of his combined pastorate seem practically immeasurable to me.

If you click on “View Larger Map” below, you can look in more detail at the geography of my grandfather’s nearly sixty-year ministry.

In 1962, Russell and Prudence moved to Richmond, Virginia, where their eldest daughter Helen and her family lived. They bought a small house at 8713 Gayton Road. It was the first home they ever owned.

Still, retirement for my grandfather did not mean the end of his ministry. For the next two decades, he took on a series of short-term pastorates, including a substantial one as the founding pastor of Huguenot Road Baptist Church in Richmond, where he served from 1964 to 1967. During the Richmond years, my grandmother taught English at a private girls’ school.

Meanwhile, my grandparents enjoyed their growing family. In the photograph below, taken at Ocean Isle Beach in North Carolina sometime in the late 1960s, they are surrounded by their three daughters, their three sons-in-law, and their ten grandchildren.

Of course, there were also frustrations in retirement, especially concerning the increasingly strident political stance of the Southern Baptist Convention. Throughout the 1960s and ’70s, the leaders of the denomination moved the group in ever more conservative directions; the 1979 convention in particular saw the organization take a hard right turn. My grandfather became increasingly disenchanted not only with the SBC but with the direction taken by Southwestern Seminary in Texas. At some point, he and my grandmother stopped sending annual donations to the school and began to support a local, independent Baptist seminary in Richmond.

Meanwhile, the Baptist churches of their daughters, First Baptist in Raleigh and River Road in Richmond, gradually moved toward independence from the SBC. In 1998, my childhood church, First Baptist of Raleigh, officially left the Southern Baptist Convention, frustrated with the national group’s political and doctrinal conservatism, especially on such issues as the ordination of women. Although he died in 1985, I think my grandfather was troubled by the stridency of the SBC in the later twentieth century.

But by then, Russell and Prudence had lived a long life of faith and service. There’s a line in Gilead that I always thought summed up well their generation: “To be useful was the best thing the old men ever hoped for themselves, and to be aimless was their worst fear.” My grandparents had certainly been useful – though it was nice that, at the end of their lives, they could relax a little.

Russell William Wallis died on Wednesday, March 27, 1985, in Richmond. He was 88 years old and survived by his wife, three daughters, three sons-in-law, ten grandchildren, and one great-grandchild (there are now 17 great-grandchildren). Prudence died a decade later, on January 27, 1995. She was 90 years old.

Soon after suffering from a stroke in early 1985, my grandfather was lying in a hospital bed in Richmond, his three daughters by his side. A doctor came in to check on him. He greeted everyone present, perhaps made a little small talk, then walked to my grandfather’s bedside, picked up his hand, and looked into his eyes.

Soon after suffering from a stroke in early 1985, my grandfather was lying in a hospital bed in Richmond, his three daughters by his side. A doctor came in to check on him. He greeted everyone present, perhaps made a little small talk, then walked to my grandfather’s bedside, picked up his hand, and looked into his eyes.

“Dr. Wallis, how are you doing today?” My grandfather, I am told, looked at him blankly.

“Dr. Wallis, do you know what year it is?” Nothing.

“Do you know who the president is?” My grandfather stared back without making a sound.

There was a pause, as the doctor searched for a flicker of understanding behind the eyes of his patient. “Dr. Wallis, do you remember the Twenty-third Psalm?”

My grandfather’s head dropped back softly onto his pillow, and he recited the whole chapter in a voice clear and strong,

1 The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want.

2 He maketh me to lie down in green pastures: he leadeth me beside the still waters.

3 He restoreth my soul: he leadeth me in the paths of righteousness for his name’s sake.

4 Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.

5 Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies: thou anointest my head with oil; my cup runneth over.

6 Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life: and I will dwell in the house of the Lord for ever.

Amen.

Works Cited

For help preparing part two of this post, I am grateful to my aunts Helen Louise Wallis Rusher and Elizabeth Ann Wallis Stephenson, my mother Nancy Jo Wallis Fleming, and my father Robert Henry Fleming.

Charles Chaney’s article “Diversity: A Study of Illinois Baptist History to 1907” appeared in Foundations: A Baptist Journal of History and Theology, 7 [Jan. 1964]: 41-54. I was also aided by Lamire H. Moore’s Southern Baptists in Illinois (Nashville, TN: Benson Printing Co., 1957).

The History of Ewing College by Dr. A. E. Prince was published in Collinsville, Illinois, in 1961 by Herald Printing Co.

The History of Kaskaskia Baptist Association, 1840-2000, which includes information about Mulberry Grove Baptist Church, can be found here.

H. Lee Swope’s History of First Baptist Church, Marion, Illinois, 1865-1965 was published by that church in 1965.

Victor Edsel Mantiply’s History of Moffett Memorial Baptist Church: Danville, Virginia, 1887-1987, was published by the church in 1987.

For more information about Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, click here and here.

For more information about the Southern Baptist Convention, click here, here, and here.

For more information about the SBC’s “Baptist Faith and Message,” click here.

The quotation from the 1912 History of Southern Illinois can be found here.

“The Rise of Fundamentalism” by Professor Grant Wacker of Duke University’s Divinity School can be found here.

The Wikipedia article on “Christian Fundamentalism” can be found here. I also relied on Encyclopedia Britannica’s “Christian Fundamentalism in the United States.”

The quotation from L. H. Scarborough can be found here.

More information about Rev. George W. Truett can be found here.

More information about First Baptist Church of Marion, Illinois, can be found here and here.

More information about U.S. Route 66 and its path through Illinois can be found here, here, here, and here.

More information about Moffett Memorial Baptist Church of Danville, Virginia, can be found here. Information about the June, 1971, fire can be found here.

More information about First Baptist Church of Granbury, Texas, can be found here.

More information about the 2010 closing of Park View Baptist Church in Portsmouth, Virginia, can be found here and here.

More information about First Baptist Church of Harrisburg, Illinois, can be found here.

More information about First Baptist Church of Litchfield, Illinois, can be found here and here. On Litchfield in general, click here and here.

More information about Huguenot Road Baptist Church in Richmond, Virginia, can be found here.

Gilead by Marilynne Robinson was published in New York City by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 2004.

This is an excellent post, David. It’s a beautiful story and it is beautifully written. Thank you!

Dear David, I had planned to just read for a few minutes, but could not stop until I had read the whole thing. I loved every bit. Especially the ending. Dad

Amazing work and writing, David. Thanks for telling us Granddaddy’s (and ours) story. Martha Beth

Dear Cousin David, your work means so much to my mom, your Aunt Helen, and to me. It is an amazingly thoughtful, comprehensive story of our family history. As you know, 90-year-old Helen does not do the internet, so we have cut and pasted your work into a printed version, which she keeps close by and does not hesitate to share with others. Thank you.